In Kanpur, Hindu nationalism clashes with a billion dollar industry.

“It isn’t difficult to sell a cow hide here,” a Dalit man tells me, bent over the carcass. The small field in which he stands is just off the main road, hidden by a thicket of wiry trees. The smell is overwhelming. Dogs prowl around, waiting for the skinless carcass to be abandoned. The man stands up, his white shirt unblemished from the messy work. My fixer taps my shoulder: “We need to go, it isn’t safe to be here for very long.”

The cow died the night before, hit by a car on the unlit roads of the outskirts of Kanpur. In the morning, someone from the Hindu neighborhood where the cow’s body was found called a government agency who sent the Dalit man to remove the body. Dalits are traditionally the caste responsible for the handling of dead animals. In Kanpur, a city in the north of India, the government employs them in waste management and roadkill clean-up. They skin the animals in private fields and sell the hides to local tanneries.

But Hindu nationalism is on the rise in India, making it increasingly difficult for them to do their job. This summer, in the nearby city of Lucknow, two Dalits were attacked by cow vigilantes for doing exactly that. “Do I worry?” says the man skinning the carcass, unwilling to give me his name because of safety concerns. “Yes, I worry. This is why I do things quietly, in quiet places. This is my job, it is not illegal. But still, I worry.”

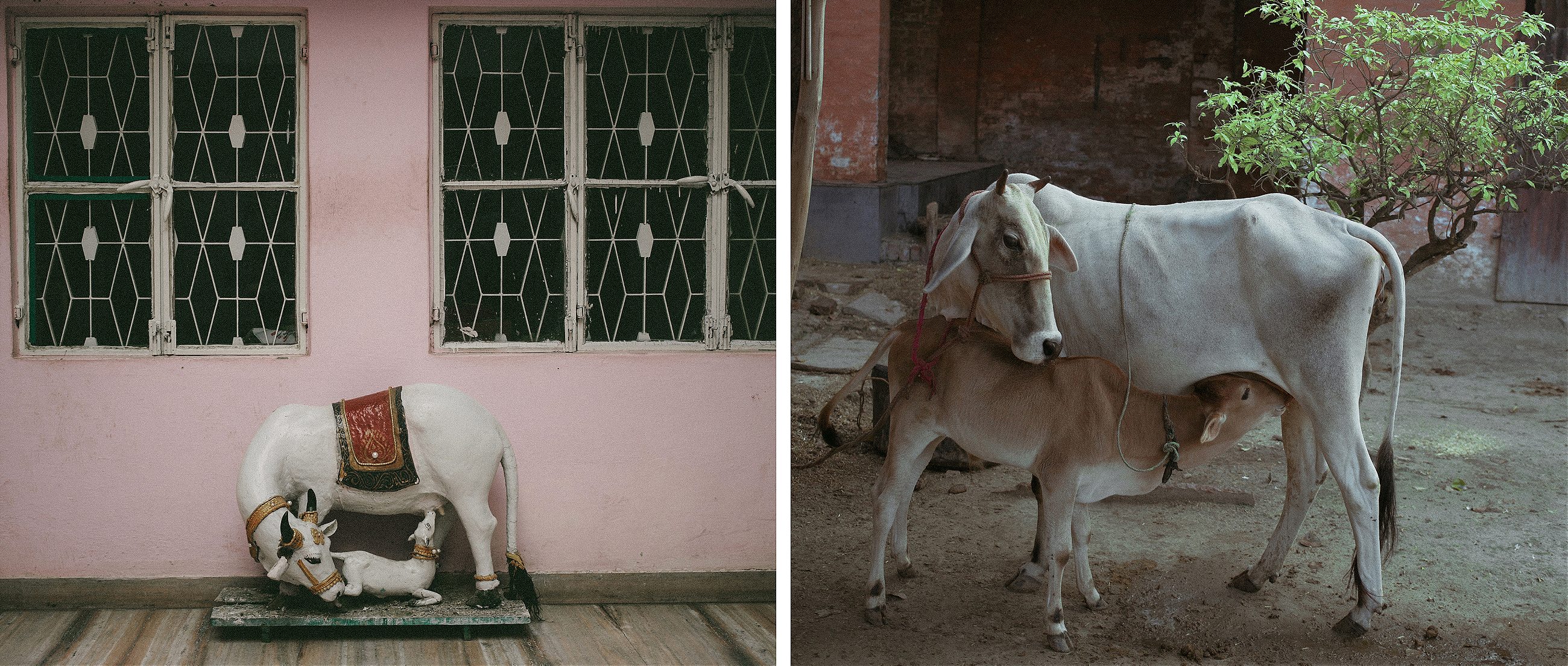

Since Narendra Modi was elected prime minister in 2014, the protection of the Indian cow has taken on a new level of intensity. While never explicitly advocating for a ban on tanneries, many feel that Modi and his Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata party are discouraging processing cattle.

In Kanpur, a city of 2.7 million people, it is illegal to slaughter a cow. Carcasses of animals that have died naturally, however, can be brought to the numerous tanneries, which are mostly owned by Muslims. Mohammed Shahav, a Muslim leather exporter from Kanpur, says that he is worried about a growing sentiment in India: that cows should be protected above people. “People are very afraid,” he says. “And our business is suffering.”

The city of Kanpur, which is 20 percent Muslim, feels like a pressure cooker. “It hasn’t happened here yet, but we watch it happen around the country. The government has supported those who murdered that man in Dadri,” says Shahav, referring to the farm worker who was killed by a mob in 2015 over rumors that his family had been storing and consuming beef at home.

Kanpur’s leather sector brings in about a billion dollars a year in export earnings. When interviewed, most tannery owners explain they only work with water buffalo hide. A few, who prefer to remain nameless, say they use hides from cows that have died naturally or that have been shipped from overseas—cows without Indian blood are not considered sacred.

Qazi Naiyer Jamal, general secretary of the Small Tanners Association of Kanpur, can talk for hours about the intricacies of this issue. A Muslim himself, he says he feels no animosity from the Hindu population of Kanpur, but adds that he has heard of many bad experiences with cow vigilantes. “People love leather belts,” he says, “but hate the people who make them.”

This reporting was supported by the International Center for Journalists.